Correct fertilisation can help

combat climate change

W

ith a growing world population

and ever increasing global de-

mand for food, it is more im-

portant than ever to maximise

crop yields and fertiliser will play a critical

role in achieving that goal. Accordingly, the

focus of greenhouse gas (GHG) reduction

efforts must be on improving the relative

carbon intensity of agricultural crops grown

with the assistance of fertilisers, rather than

on reducing absolute emissions. In other

words, efforts should be focussed on in-

creasing nutrient use efficiency without

jeopardising productivity.

It also bears emphasis that fertiliser related

GHG emissions can be substantially miti-

gated as a result of enhancing crop inten-

sity through the use of fertilisers. Fertilisers

play a key role in helping to maintain the

integrity of the globe’s forests (an essential

carbon sink) by allowing for increased pro-

ductivity on arable land, thus forestalling

deforestation and its associated GHG emis-

sions.

Fertilisers also increase the carbon seques-

tration potential of agricultural soils by con-

tributing to the building up of soil organic

matter. Increased soil organic matter gener-

ates higher nutrient uptake, and nutrients

stimulate plant growth, which, in return,

contributes to absorb more CO

2

from the

atmosphere.

Considering that global agricultural output

would be reduced by 50% without the use

of mineral fertilisers, the 2,5% of total GHG

emissions related to fertilisers seems rather

negligible – especially when compared to

the 11% directly associated with agricul-

ture and the additional 10% that relate to

forestry and other land uses. Nonetheless,

the industry is strongly committed to con-

tinue reducing fertiliser-related greenhouse

gas emissions.

Industry engagement

to limit greenhouse gas

emission

The fertiliser industry works with scientists,

producers, international organisations and

governments to develop and adopt inno-

vative agricultural practices that contribute

to reduce greenhouse gas emissions.

A large number of programmes are devel-

oped worldwide to implement soil- and

crop-specific nutrient management prac-

tices with the objective to optimise product

efficacy and minimise nutrient losses to

the environment:

Fertiliser best management practices

consist in applying the right fertiliser

source at the right rate, right time, and

right place. This initiative is called the

4Rs.

Research and training on soil analysis

allow for the development of locally

adapted protocols on application rates,

for instance in relation to the moisture

content, pH or temperature of soils.

Precision agriculture offers a range

of monitoring technologies that help

producers to apply precisely the right

amount and the right type of fertiliser.

Integrated plant nutrient management

promotes a better integration of locally

available organic nutrient sources such

as animal manure and compost with

mineral fertilisers.

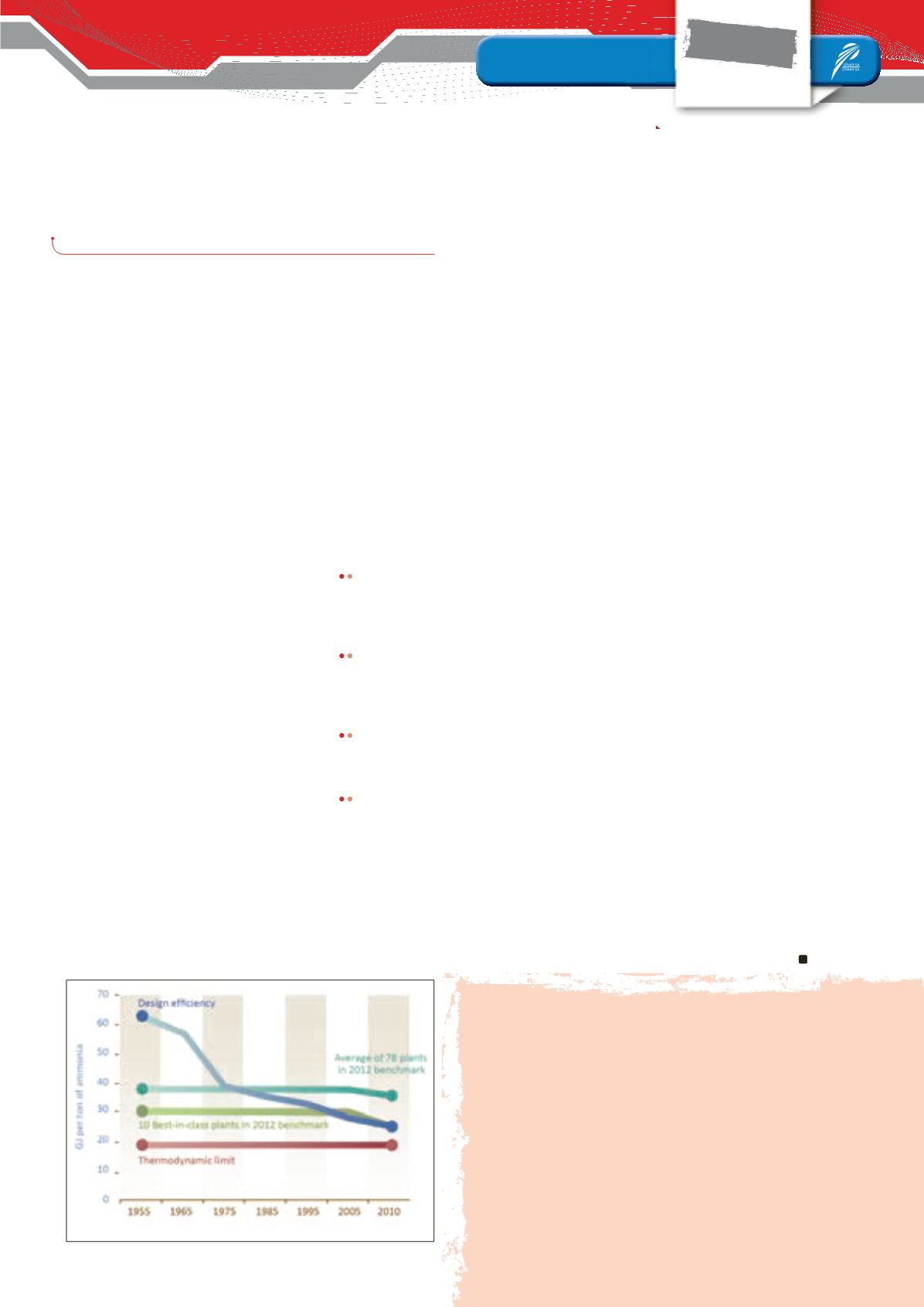

As far as production-related emissions are

concerned, fertiliser manufacturers across

the globe have been taking substantial

measures to reduce their carbon footprint

and continually strive to improve their

energy efficiency, as evidenced in IFA’s

benchmark results on energy efficiency and

greenhouse gas emissions. For instance,

consumption of energy by ammonia plants

has decreased by more than 15% over the

past decade. Overall, fertiliser production

has become increasingly efficient over the

past several decades due to the adoption

of best available technologies.

To facilitate carbon sequestration, the num-

ber one priority is to prevent further defor-

estation through sustainable intensification.

Making the most of existing farmland is es-

sential to meet the world’s food security

needs and to protect forests from being de-

stroyed, burned and converted to agricul-

tural land.

Crop yield intensification has proven to lead

to measurable carbon dioxide reductions.

However, intensification must be driven by

sustainability objectives: To that end, the

industry engages in multiple partnerships

to disseminate knowledge of responsible,

balanced and site-specific fertiliser use.

Intensification does not automatically stand

for an increase of fertilisers, but for well-

targeted use, illustrated by protocols like

‘microdosing’ (the equivalent of a full

bottle cap per seed hole) or the broad de-

velopment and marketing of ‘specialty ferti-

lisers’, such as slow- and controlled-release

fertilisers.

The ultimate aim of correct fertilisation is

to increase fertiliser uptake by the plant

while reducing losses to the environment.

For more information visit

ifa@fertilizer.org , www.fertilizer.org/NutrientStewardshipor

www.fertilizer.org//fertilizerfacts29

July 2016

FOCUS

Fertiliser

Special

INTERNATIONAL FERTILISER INDUSTRY ASSOCIATION (IFA)

Stanford study

A 2010 research study has estimated that about one billion of hec-

tares of land had been preserved from conversion to cropping be-

tween 1961 and 2005 because of advances in crop productivity,

leading to carbon emission savings of 317 to 590 Gt CO

2

-eq from not

converting that area (Burney

et al

., 2010). The authors conclude that

‘although GHG emissions from the production and use of fertilisers

have increased with agricultural intensification, those emissions are

far outstripped by the emissions that would have been generated in

converting additional forest and grassland to farmland.’

ICCA

The International Council of Chemical Associations (ICCA) squarely

puts fertilisers into the category of (chemical) products whose use

can lead to emission reductions in excess of the volume of GHG emit-

ted during their production.

Graph 1: Global energy efficiency benchmark.

Source: IFA, 2012