Oktober 2013

98

Focus on livestock

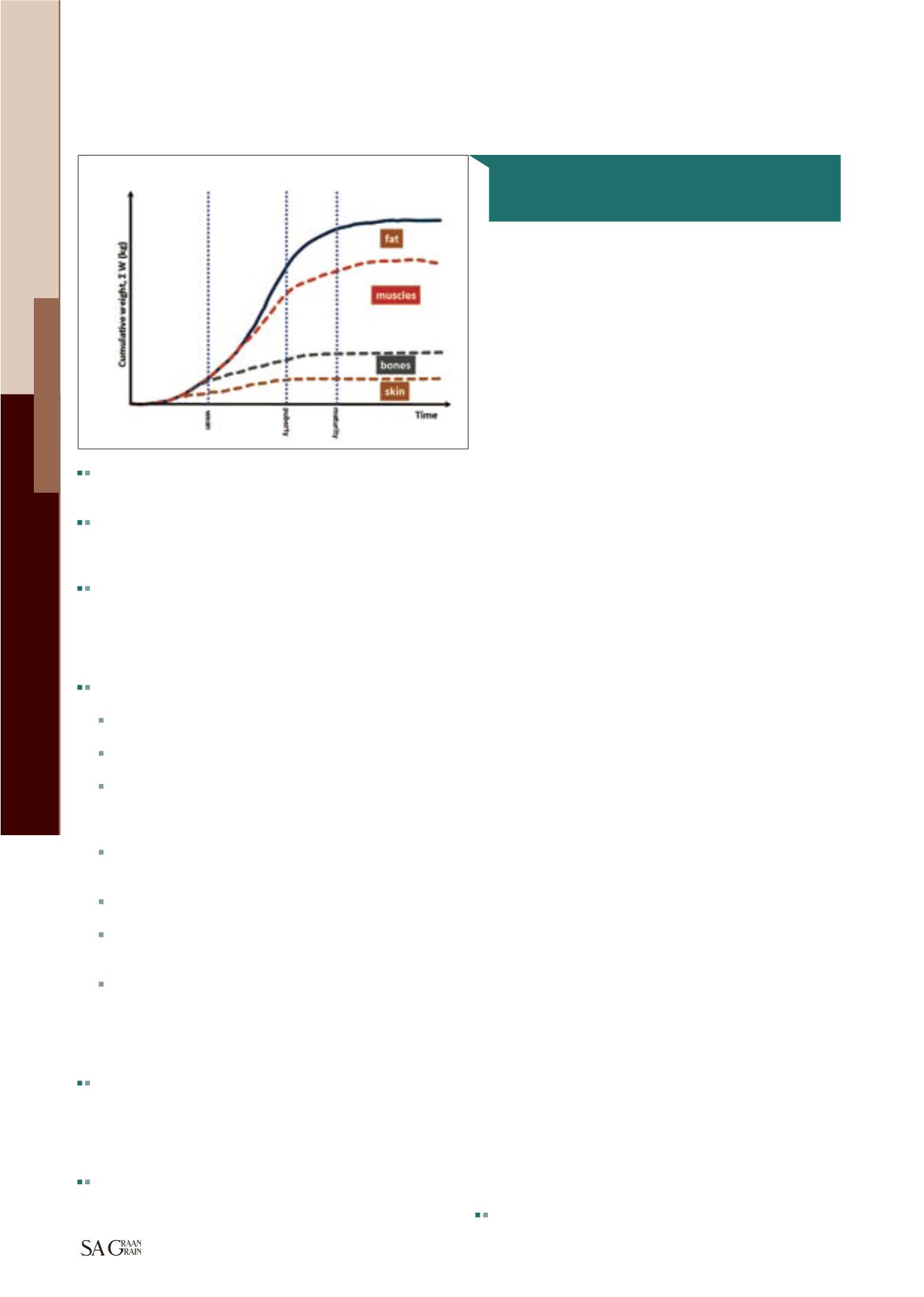

Due to the differing growth and maturity rates of bone, muscle and

fat, the percentages will also depend on the total maturity age of the

specific animal.

Classification or grading systems depending on fat cover (subcuta-

neous fat) will therefore award the same class or grade at differing

body weights in those cases where individuals differ in reaching the

desired fat cover.

Both figures depict an example of the growth curve and pattern for

an individual animal. Figure 2 indicate three important growth points,

namely weaning, puberty and maturity. The last two points espe-

cially will be later in life and at higher weights. Late maturing cattle

will therefore have less body fat at the same body weight compared

to early maturing cattle.

Later versus early maturing cattle finished in feedlots therefore impli-

cate for example:

At the same fat cover (subcutaneous fat thickness); the later ma-

turing cattle will yield larger carcasses.

At the same weight, later maturing cattle will yield carcasses with

relatively more muscle and less fat.

Later maturing cattle will generally grow faster and will generally

be better converters of high energy feed to carcass weight. This

is the result of a leaner (less fat) carcass during the feedlot period

and depositing fat at a later chronological age.

Later maturing cattle will spend a longer time in the feedlot to

reach the same carcass fat cover (as required by the classification

and price) system.

The profitability of feeding late versus early maturing cattle will

depend on the price margin and the feed margin respectively.

Generally a favourable feed margin (low grain price and high beef

price) will favour later maturing cattle. The objective is to maxim-

ise the gain (total kilograms) during the feeding stage.

An unfavourable feed margin can sometimes lead to a favourable

price margin, that is a big difference between the per kilogram

value of the weaner carcass versus the same value for the finished

carcass. In these cases the objective is to maximise the turnover

without having to put on too much gain per carcass. These condi-

tions will favour earlier maturing cattle.

The optimum carcass weight for a specific market is also very impor-

tant. The South African market is a prime example of where carcass

weights need to be within a relatively narrow weight range to secure

maximum prices per kilogram. This is generally in contradiction with

many global markets where bigger carcasses are favoured due to the

lower per unit costs (per carcass costs) in meat processing plants.

Due to the preference of an optimum carcass weight range, linked to

an optimum (mm) fat cover and age restriction (A or A/B classifica-

tion) there is also a limit on the range of maturity types suitable.

Other perspectives

The largest majority of the breeding cattle are dependant on natural graz-

ing or planted pasture. This also places more perspective on the value of

maintenance requirements of cattle under conditions of limited feeding,

both in terms of quantity and many times also quality.

It is also a known fact that the first very important function to suffer from

low levels of energy and protein feeding will be reproduction.

Figure 4

illustrates the priority in nutritional needs and the impact of nutritional

state on the allocation of nutrients in cattle.

Figure 4 indicates that, in order for an animal to survive, there will be

priorities in the allocating of nutrients to different bodily functions. Obvi-

ously, the most important will be the maintenance of crucial bodily func-

tions (such as the brain, liver, heart, etc.).

Due to the order of development, as illustrated in Figures 2 and 3, the

order of allocation will follow the developmental path of bone, muscle

and fat. In cases where the maintenance requirements are high, the other

bodily functions will suffer or will not function properly.

It can generally be stated that later maturing animals, due to bigger body

sizes, will have bigger maintenance requirements. Furthermore, in cas-

es of lower grass cover (droughts, for example) more energy is needed

to ensure rumen fill (animals need to walk longer distances to take in

enough grass) needing more energy and therefore elevating metabolism

and subsequently maintenance, even more.

Cattle that are ill adapted (the anatomical and physiological process is not

in tune with environmental constraints such as high/low temperatures,

humidity, external/internal parasites, etc.) will result in the animal to

suffer even more, often elevating the maintenance requirements further.

The reproductive rate in females (heifers and cows) is influenced by the

energy levels in the body, as dictated by the total body fat. In these ex-

treme cases where the animal is unable to take in enough or the quality of

feed is inadequate, the reproduction process will be halted.

It is therefore important for primary producers to take the maintenance

requirements of breeding females into consideration, while at the same

time producing an acceptable product to the feedlots or other finishing

units.

The genetic selection focus of primary producers should still, in order of

importance, be:

Reproduction efficiency (including ease of calving).

Continued from page 97

Making sense out of maturity

types in beef cattle

Figure 2: Total (cumulative) body weight changes and relative weight

contribution in skin, bones, muscles and body fat over time for indi-

vidual growing cattle.