ႃႉ

CHAPTER 2

• All maize producers and buyers had to be registered with the Maize Board.

• No control would be exercised over grain silo owners with respect to the storage

of maize, and remuneration rates for storage would be determined by agreement

between the parties.

• Producers could sell their maize directly to buyers and prices were determined

by agreement between buyers and sellers.

• There was no restriction on the buying and selling or even importing of maize,

provided the imported maize complied with certain sanitary and phytosanitary

standards.

• Producers who supplied maize in the export pool received an advance/ton

on delivery, and after the final completion of the pool the surplus was divided

among them by way of a final payment on the basis of tons delivered.

In the next marketing season these arrangements were amended further to permit

the free exporting of maize too, subject to the acquisition of an export permit from

the Maize Board and the payment of an export levy. In that season the Maize Board

marketed only maize that was delivered in the export pools.

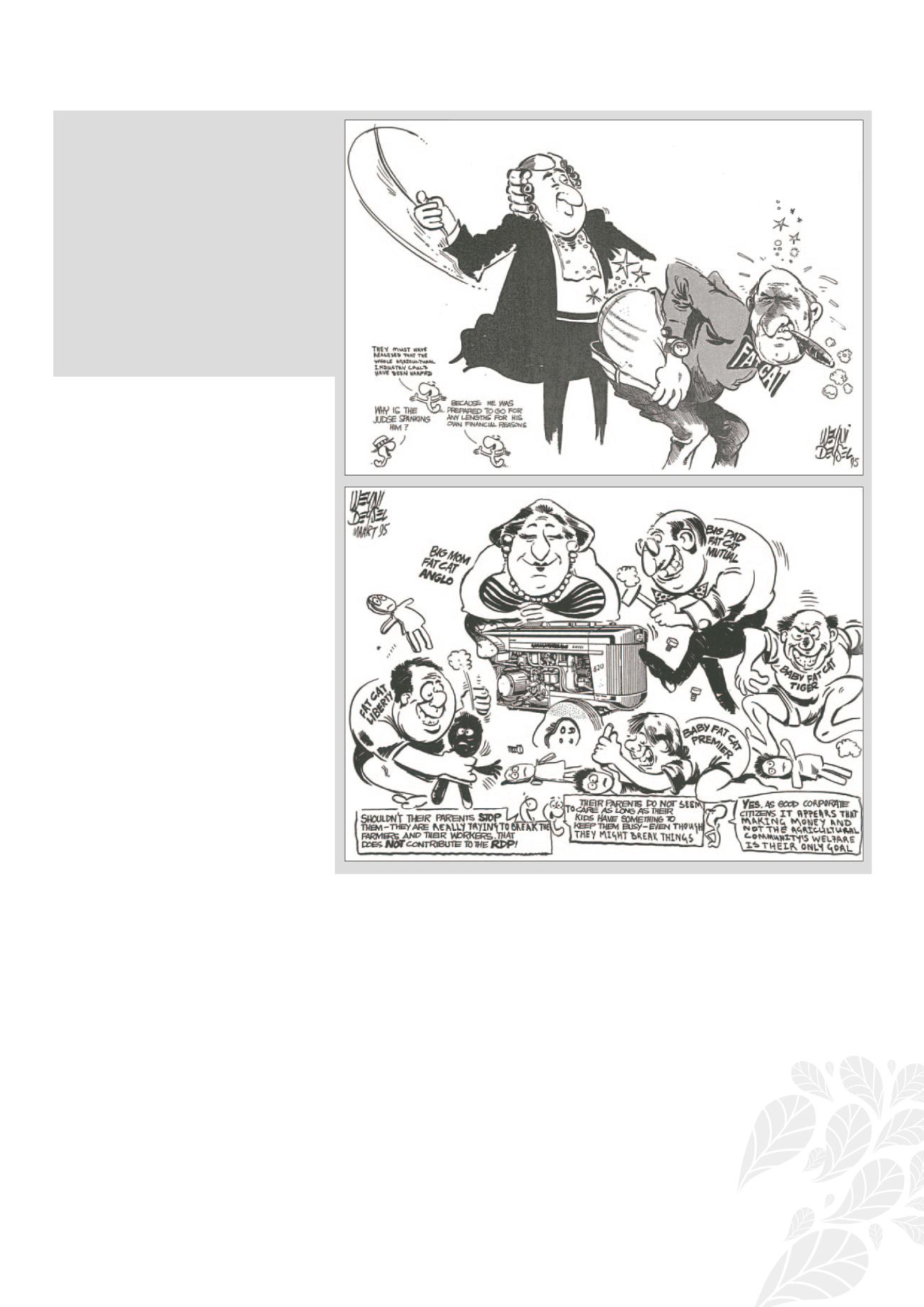

MAIZE TRUST/CBG COURT CASE

In protest against the high levies a number

of the biggest maize buyers (the Concerned

Buyers Group – also called the Fat Cats [see

cartoon alongside]) inititated a court appli-

cation in 1994 to have certain of the condi-

tions of the Summer Grain scheme declared

unconstitutional, as well as an application

for an interdict to prevent the Maize Board to

collect levies on certain maize transactions.

The application was unsuccessful. This way

the ‘country’s biggest maize buyers were

prepared to disrupt the total agricultural

industry for their own personal gain (from

Mielies/Maize

, January 1995).